Kindling a Flame or Filling Vessels: Critical Analysis and Reflection of the Application of Learning Theories in an Adult Learning Context in Medical Administration

Introduction

For many years psychologists and theorists have sought to comprehend how people learn, permeating the field of education with an array of theories. Learning is defined as ‘a relatively permanent change in human disposition or capability that is not ascribable simply to processes of growth’ (Gagné, 1985, p. 2). Acquiring knowledge ensues experiential learning (Kolb, 1984) and is dependent on prior learning and experiences (Merriam & Bierema, 2013). Consequently, learning has been viewed as a product and/or a process. Learning theories do not dispute one another but exemplify the different viewpoints which have evolved over the years (Merriam, 2004).

However, the challenge faced by the educational practitioner is to decipher these theories and ascertain related strategies to be efficaciously applied. The purpose of this paper is to reflect on my journey by critically analysing applied theories so as to inform my current practice and future journey. Facilitating a more conducive learning environment to enable my learners to learn to their full potential is paramount. As noted by John Holt (as cited in Nussbaum-Beach, 2012, p.46) ‘learning is not the product of teaching. Learning is the product of the activity of learners’. This paper proposes to question this adage.

The discipline discussed relates to a medical administration program in Cork Training Centre, comprising of several modules organised in a modular curriculum with linear sequencing (See Appendix I). This format is a prerequisite of the FETAC awards system in the centre (NUI Galway, 2013). Learning outcomes and assessments are designed by the centre with the trainer determining the teaching strategies. Moreover, as the practice is related to training and adult learning it is imperative to apply relevant theories to this cohort.

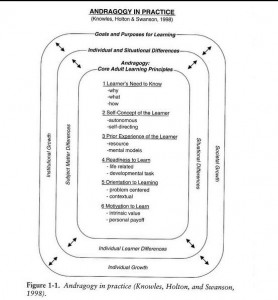

Andragogy has been defined as the ‘art and science of helping adults learn’ (Knowles, 1980, p.43). It indicates, as illustrated in Figure 1, that adults are generally more autonomous, encompass a wealth of experience, acquire a willingness to learn and are motivated problem solvers possessing a need to know approach (Jarvis, 2010). However, it has been argued that andragogy is merely a characteristic of the adult learner and does not clarify the learning process (Pratt, 1993). Therefore, for the purpose of this paper andragogy will be used as a parameter to encapsulate the characteristics of the adult learner.

The following will discuss my journey with regard to the application of learning theories in the practice reflecting on strategies pertinent to the adult learner. It will begin with behaviourism, cognitivism and finally constructivism. Furthermore, it will determine if kindling a flame or fillings vessels is apposite.

Figure 1 – Andragogy in Practice Model

Source: Knowles, Holton, Swanton (2015, p.6)

Application of Theories to Practice

Beginning of My Journey

Behaviourism stems from the work of Pavlov and Skinner where association exists between stimulus and response. If the observed behaviour is rewarded it is expected to reoccur and improbable if reward or reinforcement is absent (Jarvis, Holford, & Griffin, 2003). Therefore, responses are learned and governed by the consequences and environment. This theory is evident in adult education as it focuses on providing learners with skills for specific industries where they will be expected to be competent in performing these skills (Merriam & Bierema, 2013).

The behaviourist theory dominated my association with education and classroom prior to becoming an educator. Consequently, being conditioned to this theory, embracing the role of the trainer delivering to passive learners, was inevitable. For example, the module Text Production is governed by the learning outcome of inputting text accurately from source within a specified time. Strategies implemented to progress learners from beginners to experts include: step by step instruction, short practice drills while substantiating reinforcement with feedback (Jordan, Carlile, & Stack, 2008).

However, as the focus is on the external environment the internal thoughts of the subject can be disregarded (Merriam & Caffarella, 1999). While the learners may successfully demonstrate the learning outcome do they critically analyse the content and layout? Inaccuracy in medical documents can be detrimental. Consequently, it implies that the theory may be valid for the product, but not the actual learning process. Adult learners covet problem solving in real life situations (Knowles, 1984). Furthermore, adult learners are autonomous whereas the pedagogical application of behaviourist theory is control (Wenger, 2009).

Path Beyond Behaviourism

In contrast to the behaviourism theory cognitivism associates learning with effectively processing and organising information. As the course is designed in a modular curriculum it reduces cognitive overload as it is designed into manageable chunks (Weegar & Pacis, 2012). Furthermore, there is a parallel structure between the complex modules to optimise learning. For example, Word Processing and Anatomy & Physiology modules are delivered concurrently (See Appendix II). Conversely, educators can enhance learning by creating activities to augment cognitivism (Jordan et al, 2008). Activities include short lectures and modicum material to avoid short term memory overload, pneumonics and presenting topics in different formats to transfer to long term memory (Carlile & Jordan, 2005). However, as an educator it is important to value learning outcomes, reinforcement and ‘behaviour modification in structuring learning activities for adults’ (Merriam & Bierema, 2013, p. 28).

In structuring lesson plans for this course Gagné’s Nine Events of Instruction is applied to enhance the learning which promotes a systematic process to stimulate desirable behaviour taking cognitive fundamentals into consideration (Jordan et al, 2008). Prior experience and learning supportively impacts long term memory (Knowles, Holton, & Swanson, 2015). Table 1 depicts the relationship between the event and learning process and examples of its application in the medical administration course for adult learners. Kellers ARC Model of Motivation has also been implemented to illustrate how these events promote motivation (Maria & Gabriel, 2011). Adult learners are intrinsically motivated and yearn recognition for their efforts (Blondy, 2007).

Table 1 – Gagné’s Nine Events of Instruction

| INSTRUCTIONAL EVENT | Relation to Learning Process | Application of events in Customer Service Module | ARCS Model | |

| Gaining attention | Reception of patterns of neural impulses | Watch video on impact of body language in medical sector which will identify a gap in their knowledge. Adults learning is more related to life than to the actual subject (Knowles, 1984). | Attention | |

| Informing the learner of the objective | Activating a process of executive control | Cleary describe learning outcomes for lesson and how they will be useful in their sector. Adults want to know what they are learning and why (Knowles, 1984). | Relevance | |

| Stimulating recall of prerequisite learned capabilities | Retrieval of prior learning to working memory | Ask questions about their perceptions and prior knowledge on body language and provide learners with advance organisers. Adults come with a vast resource of experiences (Knowles, 1984). | ||

| Presenting the stimulus material | Emphasizing features for selective perception | Describe history and importance of body language. Deliver in small chunks on microexpressions and use examples in visual format. | ||

| Providing learning guidance | Semantic encoding; cues for retrieval | Recap information to ensure understanding from learners. Ask students to draw a picture of a person they would consider to have positive body language and negative body language. Compare and discuss. Drawing pictures can assist in storing information creating stronger visual (Carraway, 2014). | Confidence | |

| Eliciting performance | Activating response organization | Practical assignments for learners to complete. Get students to role play customer service scenarios and/or create a script. Monitor learners.

Adult learners are self-directed and autonomous (Knowles, 1984). |

||

| Providing feedback about performance correctness | Establishing reinforcement | Monitor and give constructive feedback on one to one basis. This promotes motivation. | Satisfaction | |

| Assessing the performance | Activating retrieval; making reinforcement possible | Assess performance of exercise against learning outcome by giving learners an assessment. | ||

| Enhancing retention and transfer | Providing cues and strategies for retrieval | Discuss how they will implement their new skills into their work environment. Adult learners are life-centred (Knowles, 1984). |

Source: based on Gagné et al, (2005, p. 195)

In addition, the presence and order of all events for each lesson is flexible (Gagné, Wager, Golas, & Keller, 2005) which is paramount where lessons can equate to 6.25 hours. However, Gagné’s events have been disputed by constructivist theorists inferring its lack of learner-centred approach, interaction and reflection (Hricko, 2008). Furthermore, Briggs Instructional Design in Table 2 suggests that this course is significantly teacher centred.

Table 2

| Teacher Centred | ||||

| Much | Some | Little | Currently Applied in Medical Administration course | |

| Group | Lecture

Questioning Dialogues Demonstration |

Discussions

Roleplay Debate Open Forum |

Brainstorming

Buzz groups Guided Design Simulations Peer Tutoring |

Lecture

Questioning Demonstration Discussions Roleplay

|

| Individual | Individual tutoring

Dialogue Demonstration |

Guided reading

Simulation Guided practical |

Computer Aided Instruction

|

Guided practical

Demonstration

|

Source: based on Briggs (1991, p. 182)

This is further substantiated by the completion of Conti’s Principles of Adult Learning Scale (PALS) where it indicates my style as teacher-centred (See Appendix III). Literature indicates that learners ‘are not empty vessels waiting to be filled, but rather active organisms seeking meaning’ (Driscoll, 2005, p.387). For learning to occur, adult learners must reflect upon their experience incorporating cognitive, psychomotor and/or effective elements (Boud, Cohen, & Walker, 1993). Consequently, I am forced to question my strong teacher-centred approach as I continue my journey to the constructivist theory.

On the Right Path?

Misperception exists with regard to the definition of constructivism where it is assumed that it is learner directed. However, it actively involves both the facilitator and learner (Gordon, 2009). Learners construct meaning from their experiences and andragogy is consistent with constructivism in that it draws from life experience, the cognitive processes of learners changing schema and through social interactions (Eddy, 2011). At the same time, experiential learning has been associated with constructivism where learners ‘construct knowledge by interacting with their environment through a set of perceived experiences’ with contributions from Kolb, Piaget and Dewey (Mughal & Zarar, 2011, p.28).

Several modules in the Medical Administration course are practical in nature, for example, Word Processing, Audio Transcription and Text Production which compels the individual learner to become active in constructing tasks in order to develop their skills. While existing literature on strategies in medical administration are marginal and outdated, experiential learning is significantly denoted in medical education due to development and application of competences (Taylor & Hamdy, 2013). This resonates with Kolb’s Experiential Theory as illustrated in Figure 2 which enables the learning process to ensue (Kolb, 1984). However, due to the behaviourist approach its application in this course is predominantly on Concrete Experience and Active Experimentation.

Figure 2 – Kolb’s Reflective Learning Cycle

Source: Merriam & Bierema (2013, p.125)

However, the application of reflective observation and abstract conceptualisation could facilitate learners in reflecting and concluding on the layout, content and relevance of the event. For example, following a demonstration on medical referral letters, learners could be asked to reflect on the layout and inaccuracies whilst constructing recommendations and connections to medical terminology. According to Bandura imitation promotes learning, therefore, carrying out the demonstration would be constructive to the learning process (Jordan et al, 2008). Implementing group discussions on a relevant case study followed by a practical exercise would promote reflection and conclusion. However, in western society imitation has been connected to replication or a mechanical process rather than a learning process (Hoel, 1997). Nonetheless, imitation facilitates learners by actively building on existing knowledge whilst creating connections and social interaction (Gordon, 2009).

Encompassing all learners in discussion in the classroom promotes a social element thus augmenting learning which resonates with Vygotsky and social constructivism (Jordan et al, 2008). Reflection and concluding can initiate learner decision making which is pertinent to the adult learner who is self-directed with a yearning to solve problems in real life situations (Knowles, 1984). In medical education many outcomes are related to attitudes in contrast to knowledge (Taylor and Hamdy, 2013).

Attributable to diversity and different learning styles some adult learners are not self-directed and resist new information as it contests their existing schema (Knowles et al, 2015). For example, some adults have been conditioned to sit back and expect to be taught. Prior negative experiences may obscure their association with education resulting in a deficiency in self-direction and autonomy. Therefore, it is paramount that the strategies employed by the educator are encouraging and relevant (Knowles, 1980). In addition, creating an environment that is amenable with a sense of connection and variety is paramount in the classroom (Merriam, 2004).

Constructivism views the role of the educator as a facilitator and distinctive strategies include the promotion of self-direction where learners are encouraged to answer questions, articulate their own ideas, thoughts and conclusions (Weegar & Pacis, 2012). This resonates with andragogy. Furthermore integrating constructivist activities with Gagné’s Nine Events of Instruction could provide a solid framework (Stollings, 2007). Table 3 illustrates several constructivist activities that could be applied to each event to facilitate a conducive learning environment for adult learners. Some of these proposed activities have been applied to the existing lesson plan (See Appendix IV).

Table 3

| INSTRUCTIONAL EVENT | Constructivist Activities |

| Gaining attention | · stimulate learners curiousity with questions

· present meaningful and relevant challenge |

| Informing the learner of the objective | · this can be a general goal that is then personalized by the learner

· utilize problem based learning |

| Stimulating recall of prerequisite learned capabilities | · students can tie new learning to past constructions of knowledge

· incorporate the use of concept maps |

| Presenting the stimulus material | · facilitate student ownership of learning material

· have students create authentic material ie. web-sites, blogs, hypertexts · provides spaces for students to construct knowledge · provide models · create Microworlds · incorporate games |

| Providing learning guidance | · provide guiding questions

· utilize zones of proximal development · provide for scaffolding · set up communities of learners · incorporate knowledge building networks · provide authentic problem-based tasks around existing software packages and forms of “Edutainment” · provide spaces for inquiry |

| Eliciting performance | · incorporate Wikis

· encourage interactivity through the use of social software like Skype |

| Providing feedback about performance correctness | · set up chat rooms for peer feedback/collaboration

· allow students to reflect on their own learning |

| Assessing the performance | · monitor student’s progress

· have students self-assess their progress · incorporate ePortfolios |

| Enhancing retention and transfer | · once students become ‘experts’ have them coach/scaffold others |

Source: (Stollings, 2007)

In addition, providing learning guidance when required is depicted in Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (See Figure 3) where ‘development is dependent upon relationship and collaboration’ (Jarvis, 2010, p.73). It is transferable to all types of learning and activities (Engestrom, 1987). This strategy is currently being applied to this course but due to the strong behaviourism approach the removal of the scaffolding which is pertinent to the adult learner for self-directed learning is not always adhered to.

Figure 3 – Vygotskys Zone of Proximal Development

Source: Carlile & Jordan (2005, p.22)

Future Paths

As the course is structured in modular design, it facilitates learner centred approaches, for example, project work, group collaboration and practical assignments (NUI Galway, 2013). However, modules are not integrated and are deemed impartial (Tummons, 2012). For example, the module Communications is delivered in other programs ranging from legal to tourism. Thus, it does not provide an environment for the learner to integrate the medical components of the course with these modules.

Consequently, future research on the application of a coordinated curriculum may be beneficial where a link exists between subjects so ‘as to effect complementarity and interaction between subjects’ (Neary, 2003, p.116). Many reports support an integrated curriculum in medical education (Anderson & Swanson, 1993). Presently, I attempt to integrate these modules with medical elements despite not being outlined in the learning outcomes or assessment. As a result, it does not conform to constructive alignment where the teaching methods, assessment and learning activities are aligned to the learning outcomes (Biggs, 2003).

Conclusion

Behaviourism is predominately applied to the Medical Administration course for adult learners. Behaviourism and cognitivism are associated with a teacher-centred approach focusing on observed behaviour and the processing of information. Consequently, in this course theory may be valid for the product, but not always to the actual learning process. Constructivism uses a more facilitative approach where the learner is more self-directed and constructs new knowledge with old.

Furthermore, constructivism is more apt to the characteristics of the adult learner (Blondy, 2007) who is autonomous, has a willingness to learn with a desire to solve problems (Knowles, 1984). It resonates with John Holt where learning relates to the activity of the learners, however, this paper suggests that all theories discussed require teaching whether it be facilitative or directed. However, while a humanistic student-centred approach is relevant to adult learning, other aspects of teaching may be required in the classroom (Jarvis, 2010). This paper suggests that applying behaviourist, cognitive and predominantly constructivist activities into Gagné’s Nine Events of Instruction may create an environment that will kindle the flame for adult learners as oppose to just filling empty vessels. This resonates with the aim of the centre which is ‘to give learners a second-chance education in a non-threatening environment that is learner centred’ (Qualifax, n.d.).

While my journey turns to a more facilitative role, an observation has been made on the outdated or marginal research on this cohort. Therefore, future research is recommended, principally on the existing curriculum design where each module is impartial. Questioning the application of a coordinated curriculum with a medical theme may be beneficial to ensure that the flame burns even brighter.

References:

Anderson, M. B., & Swanson, A. G. (1993). Educating medical students: The ACME-TRI report with supplements. Acad Med, 68(4), S1-S46.

Biggs, J. B. (2003). Teaching for quality learning university (2nd ed.). Buckingham: Open University Press/Society for Research into Higher Education.

Blondy, L. C. (2007). Evaluation and Application of Andragogical Assumptions to the Adult Online Learning Environment. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 6(2), 116-130.

Boud, D., Cohen, R., & Walker, D. (1993). Introduction: Learning from Experience . In D. Boud, R. Cohen, & D. Walker, Using Experience for Learning. Buckingham, UK: SRHE and Open University Press.

Briggs, L. J. (1991). Instructional Design: Principles and Applications. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Educational Tecnology Publications.

Carlile, O., & Jordan, A. (2005). It works in practice but will in work in theory? The theoretical underpinnings of pedagogy. Emerging Issues in the Practice of University Learning and Teaching, 11-26.

Carlile, O., & Jordan, A. (2005). It works in practice but will it work in theory. In G. Moore, & B. McMullin (Eds), Emerging issues in the practice of university learning and teaching (pp. 11-26). Dublin: AISHE.

Carraway, K. (2014). Transforming Your Teaching: Practical Classroom Strategies. New York: W W Norton & Company Inc.

Driscoll, M. P. (2005). Psychology of learning for instruction (3rd ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Eddy, P. (2011). The Story of Charlotte: An Adult Learner’s View of Higher Education. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 49(3), 14-20.

Engestrom, Y. (1987). Learning by Expanding. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit.

Gagné, R. (1985). The Conditions of Learning (4th ed.). New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Gagné, R. M., Wager, W. W., Golas, K. G., & Keller, J. M. (2005). Principles of instructional design. Toronto: Thomson Wadsworth.

Gordon, M. (2009). The misuses and effective uses of constructivist teaching. Teachers and Teaching: theory and practice, 15(6), 737-746.

Gordon, M. (2009). The misuses and effective uses of constructivist teaching. Teachers and Teaching, 15(6), 737-746.

Hoel, T. L. (1997). Voices from the classroom. Teaching and Teacher Education, 13(1), 5-16.

Hricko, M. (2008). Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction. In L. A. Tomei, Encyclopedia of Information Technology Curriculum Integration (pp. 353-356). Hershey: Informtion Science Reference.

Jarvis, P. (2010). Adult Education and Lifelong Learning (4th edn ed.). Oxon: Routledge.

Jarvis, P., Holford, J., & Griffin, C. (2003). The theory & practice of learning (2nd ed.). London: Kogan Page Limited.

Jordan, A., Carlile, O., & Stack, A. (2008). Approaches to Learning . Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Knowles, M. (1980). The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy. New York: Cambridge Adult Education.

Knowles, M. S. (1984). Andragogy in Action. San Fransicso: Jossey-Bass.

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2015). The Adult Learner (8th ed.). Oxon: Routledge.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Maria, T., & Gabriel, T. (2011). The impact of the interactive-motivational training model on optimizes adult motivation within the process of vocational training. Journal of Educational Sciences, 13(2), 43.51.

Merriam, S. (2004). The changing lanscape of adult learning theory. In J. Comings, B. Garner, & C. Smith, Review of adult learning and literacy: Connecting research, policy and practice (pp. 199-220). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Merriam, S. B., & Bierema, L. L. (2013). Adult Learning Linking Theory and Practice. San Fransciso: John Wiley & Sons.

Merriam, S., & Caffarella, R. (1999). Learning in Adulthood. San Fransicso: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Mughal, F., & Zafar, A. (2011). Experiential Learning from a Constructivist Perspective: Reconceptualizing the Kolbian Cycle. International Journal of Learning & Development, 1(2), 27-37.

Neary, M. (2003). Curriculum Studies in Post-complusory and Adult Education. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes Ltd.

NUI Galway (2013). Course Design. Galway: NUI Galway.

Nussbaum-Beach, S. (2012). The Connected Educator. Bloomington: Solution Tree Press.

Pratt, D. D. (1993). Andragogy after twenty-five years. In S. B. Merriam (Ed), An update on adult learning theory (pp. 15-23). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Qualifax. (n.d.). Second Chance and Further Education. Retrieved from Qualifax: http://www.qualifax.ie/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=143&itemid=190

Stollings, L. (2007). Robert Gagné’s Nine Learning Events: Instructional Design for Dummies. Retrieved from University of British Columbia: http://etec.ctlt.ubc.ca/510wiki/Robert_Gagne%27s_Nine_Learning_Events:_Instructional_Design_for_Dummies

Taylor, D., & Hamdy, H. (2013). Adult learning theories: Implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Medical Teacher, 35(1), e1561-e1572.

Tummons, J. (2012). Curriculum Studies in Lifelong Learning Sector. London: SAGE Publications.

Weegar, M. A., & Pacis, D. (2012). A Comparison of Two Theories of Learning – Behaviorism and Constructivism as applied to Face-to-Face and Online Learning. E-Leader Manila. Retrieved October 10, 2015, from http://www.g-casa.com/conferences/manila/papers/Weegar.pdf

Wenger, E. (2009). A social theory of learning. In K. Illeris, Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning Theorists (pp. 209-218). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.